Wires across the Strand

You know, of course, of The Strand Magazine's most famous contents: Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories, illustrated by Sidney Paget. This renowned association makes the Strand a familiar periodical to many readers today, but the Strand exceeds merely housing Holmes. It became a desirable site for short fiction by many writers; indeed from 1910 in England P.G. Wodehouse wrote stories exclusively for the Strand. [1] At the same time it offered fiction in translation, reports on everything from animal hospitals to christmas crackers, illustrated interviews, portraits of celebrities, facsimilies of handwritten texts, and even stories for children. As part of my contribution to our on-going archival research for Scrambled Messages, I return to its pages, going right back to its first year of publication, 1891. The appearances of the telegraph in the Strand suggests some lines of further enquiry for us Scrambled Messagers.

You know, of course, of The Strand Magazine's most famous contents: Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories, illustrated by Sidney Paget. This renowned association makes the Strand a familiar periodical to many readers today, but the Strand exceeds merely housing Holmes. It became a desirable site for short fiction by many writers; indeed from 1910 in England P.G. Wodehouse wrote stories exclusively for the Strand. [1] At the same time it offered fiction in translation, reports on everything from animal hospitals to christmas crackers, illustrated interviews, portraits of celebrities, facsimilies of handwritten texts, and even stories for children. As part of my contribution to our on-going archival research for Scrambled Messages, I return to its pages, going right back to its first year of publication, 1891. The appearances of the telegraph in the Strand suggests some lines of further enquiry for us Scrambled Messagers.

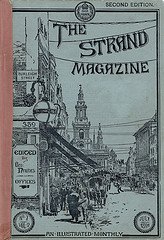

The front cover of the Strand ties this magazine to the telegraph as its title's letters hang from telegraph wires across the page, wires that criss-cross their way into the distance. Thus each monthly issue always associates telegraphic communication, concise, fast, direct, with the Strand’s contents. The spectacle of suspended telegraphic communication speaks to our project. Whilst these urban wires serve as a visual reminder of the passage of messages, the transatlantic cable sits submerged beneath the waves and hence the visual spectacle of messages passing from one side of the ocean to the other must lie elsewhere.

Moving inside the cover, in multiple illustrations depicting The Strand in 1890, telegraph wires also pervade the very first article of the first ever issue: ‘The Story of the Strand’ (pp. 4-13. Access this article here). This article serves to firmly associate magazine with particular place. The text and illustrations focus the reader on two aspects of the street, progress and connectedness, thus making the association between these things and and the periodical itself. The text narrates the histories and past scandals associated with the many great buildings that run along this thoroughfare, ‘the most interesting street in the world’. Yet of the nine accompanying images, five portray the almost present. Of these, four clearly show telegraph wires stretching off beyond the confines of the illustrations’ frame. Whilst the text connects the publication with progression (‘it would be impossible to find a street more entirely representative of the development of England’), the illustrations emphasise the Strand (and so the Strand)’s contemporary connectedness as a site into which information flows and from which it transmits. Connectedness possesses value.

Once the first issue makes this connection, however, the telegraph plays a different role amongst the Strand's subsequent numbers. In the next month’s issue the telegraph appears in ‘A Night with the Thames Police’ (pp. 124-132. Access this article here). The inclusion of the telegraph in this reporter’s account seems out-of-place, interruptive. As the reporter visits the Thames police's principal station, in the High Street, Wapping, he notes:

‘Just in a crevice by the window are the telegraphic instruments. A clicking noise is heard, and the inspector hurriedly takes down on a slate a strange but suggestive message.

'“Information received of a prize-fight for £2 a side, supposed to take place between Highgate and Hampstead.”

'What has Highgate or Hampstead to do with the neighbourhood of Wapping, or how does a prize-fight affect the members of the Thames police, who are anything but pugilistically inclined? In our innocence we learn that it is customary to telegraph such information to all the principal stations throughout London. The steady routine of the force is to be admired.’ (p. 127)

Much in this short intrusion intrigues me: the ephemerality of the message, noted on a slate and so sure to be erased at a later moment; the fact that the inspector, amongst all his responsibilities, also can read a telegraphic message; the idea that all police intelligence throughout London interrupts all police stations regardless of location; and the effect of the inclusion of this ephemeral irrelevant message itself on the text. The reporter admires this interruption where we would frown on its inefficiency. Equally, in never developing into further narrative, this intrusion seems inefficient reporting on the journalist's behalf.

Aside from a background appearance in Grant Allen's story 'Jerry Stokes' in March, the telegraph then disappears from inside the Strand and we even find that its conspicuous absence stands out from 'A Silver Harvest', a short piece on cornish pilchard fishing that appears in the June edition (pp. 634-637. Access this article here). The sighting of the red streak of the first shoal excites communcation by simply shouting and the reporter notes that 'though the fishing villages as a rule are in communication only through coaches, or more often carts, the news of the first catch rapidly flies' (p. 635). This serves as a reminder that whilst the transatlantic telegraph cable transformed communication across great distance, many communities lacked connection to the telegraph system and so to direct experience of the immediacy of this distinctively mediated messaging.

This system returns to the Strand the next month, no longer symbol or background but as a plot device. When Sherlock Holmes declares 'I must wire the King without delay' in 'Scandal in Bohemia' (pp. 61-75 (p. 73), access this story here), Conan Doyle effects action out with the narrative itself yet essential to the plot. The telegraph facilitates the covering of distance beyond the enclosed pages of short fiction. Conan Doyle uses the telegraph to this effect in a number of other stories in 1891. In 'The Five Orange Pips' (November 1891, pp. 481-491) it enables him to reassure the reader of Holmes's intention to seek justice as he cables the U.S. police to ensure the capture of three villains, whilst never requiring a scene on the other side of the Atlantic. Similarly telegrams can draw characters into required positions within a narrative, whether one summons Watson in 'The Boscombe Valley Mystery' (October 1891, pp. 401-416) to commence the story or another effects a chance event to drive the plot of 'The Man with the Twisted Lip' (December 1891, pp. 623-637).

At this point in my investigations, the uses of the telegraph in the 1891 issues of the Strand Magazine suggest the significance both of the invisible known (the cable under the sea, the action significant to plot) and also of making the unknown visible (the police telegram, the telegram in fiction which draws a character into a chance encounter). I am interested now to return to narratives of the transatlantic telegraph itself to explore how these ideas play out there.

1. Kate Jackson, George Newnes and the New Journalism in Britain, 1880-1910 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001), p. 93.

image 'The Strand Magazine, Vol. 2, No. 7, July 1891' by Special Collections Toronto Public Library cc licence