DUPLEX TELEGRAPHY I: HIROSHI SUGIMOTO

Duplex is simultaneous communication between two points in both directions. In terms of telegraphy this means sending messages along a single wire, both ways at once. This capability was developed over several decades, becoming a practical reality in the early 1870s. So that received messages could be understood, it was necessary for both parties to cancel out their own current using matching resistance, effectively silencing their own messages so that the line appeared free to receive signals from the other end. Duplex technology often made use of the Wheatstone bridge to match the current of an outgoing message; an equal current would be automatically sent in the opposite direction at the signalling end, thereby cancelling out the initial signal and leaving the line effectively 'clear' for messages to be received.

When considering cultural materials to explore in conjunction with this technology, both for buttressing our understanding and making conceptual links (or frequently leaps!), I immediately thought of Hiroshi Sugimoto's Dioramas. The matching circuit in duplex telegraphy - the one used to silence outgoing messages at the signalling station - is frequently called 'dummy' circuit, as it plays no part in the sending and receiving of actual messages. Photography is intrinsically bound up with imitation and deception, from the panoramic and stereographic photographs of the mid-nineteenth century to the development of the (apparently) moving image from the late 1870s.

For his Diorama series, Sugimoto used photography to record another version of life in imitation, the museum diorama. With their exquisite detail and fine shading, the photographed stuffed animals look almost alive, although there is often something slightly uncanny – an intense stillness, a staged quality – about the image. In Gemsbok, for example, the tufts of grass, which seem stuck to the ground rather than growing out of it, suggest something about the scene is not quite natural. The double illusion – a staged scene to a photographic image – is part of the Dioramas’ relevance to duplex, while both dioramas and photography have their roots in the nineteenth century.

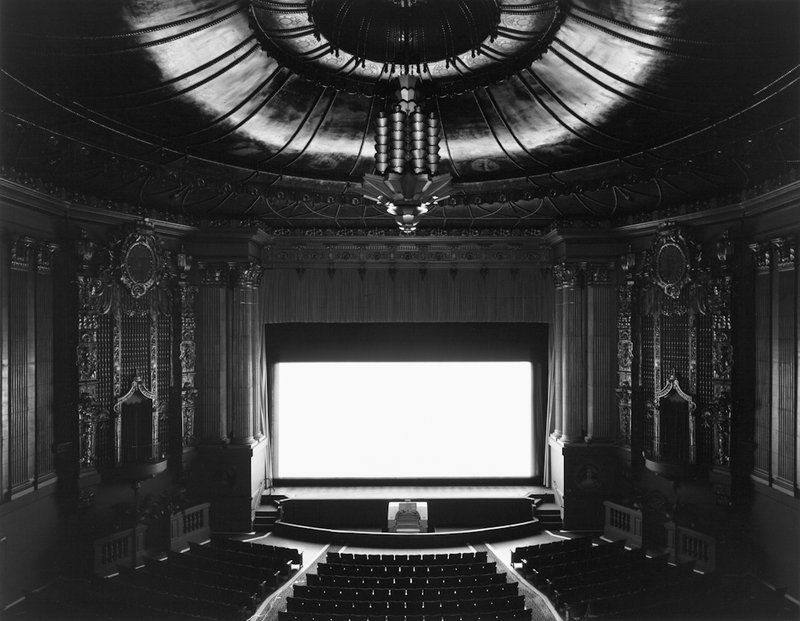

But on a more conceptual level, Sugimoto’s Theater series might have more relevance to the duplex. For Theaters, he used a slow shutter release to photograph a film playing in an empty cinema. The architecture is reproduced with monochrome intensity, while the screen forms a bright white rectangle, the images of the film having streamed through the lens without registering. The camera lens and the cinema screen create a kind of feedback loop, resulting in the visual equivalent of white noise – or, in telegraphic terms, the cancelling out of the screen’s signal, which brings out instead – literally in high relief – the symmetry and elegance of the cinema itself. It is as though camera and screen have been in communication, and the result, to human eyes, is clean white radiance, which evokes cinema’s magical power as well as offering a meditation on the differences between technological recording and human perception. The pure light of the screen, like the current in the telegraphic wire, is inaccessible to human understanding: it needs mediation, decoding.

Scrambled Messages examines the submarine cable, so I want to end with a brief consideration of the Seascapes, which are like a natural version of Theaters. They comprise topographical portraits of named seas, taken using a long exposure so that some transient details have disappeared, while the general pattern in the water remains. Both sky and water look luminous and impossibly still, their blurred horizontality reminiscent of Mark Rothko’s painting (and of course, of marine painting). Like the Theaters, the Seascapes elicit a sense of quiet awe, even of spirituality. Again, something in the scenery has been lost, or silenced, to allow something else to emerge, just as the dummy circuit silences the current. Additionally, the Seascapes articulate the overwhelming scale of open water, like that bridged by the transatlantic cable, and these environments are superficially generic and yet absolutely specific, with names, coordinates and their own distinctive character. With the lack of landmarks, of recognisable detail, the title of each Seascape – North Atlantic Ocean, Cape Breton, for example, which was on the route of the transatlantic telegraph cable – becomes more significant. The signal, with extraneous information suppressed, can be received clearly.